Pasteurellosis

A page about pasteurellosis in sheep describing cause, clinical signs, diagnosis and control.

Introduction

Pasteurellosis is a devastating condition affecting sheep of all ages. It is one of the most common causes of mortality in all ages of sheep. It is most often associated with stress. The disease is of considerable economic significance and is responsible for a high mortality rate and substantial treatment costs.

Many factors including stress and management play a role in the development of disease. The most important infectious agents involved are bacteria including Mannheimia haemolytica, Bibersteinia trehalosi and Pasteurella multocida.

Aetiology

The aetiology (cause) of pasteurellosis is multifactorial.

1. Stress – is a major predisposing factor to pasteurellosis outbreaks. Stress can arise from:

Passage through marts

Commingling

Weaning, castration

2. Infectious agents

Mannheimia haemolytica, Bibersteinia trehalosi and Pasteurella multocida are frequently isolated from the lungs of sick sheep. These pathogens are associated with a high mortality rate.

They are considered normal residents of the tonsils and throat of healthy animals. However, under stress, the immune system becomes suppressed and these bacteria can multiply. They invade the lungs and from there can either set up a pneumonia or septicaemia. If untreated, cases die rapidly. Case fatality rate with Bibersteinia trehalosi is notably higher than the other organisms.

3. Management

The environment in which animals are kept, nutrition and management of animals may all contribute to increases in pasteruellosis incidence on individual farms. These factors can add to stressors, listed above, to suppress immunity. Resistance to disease can, on the other hand, be increased through vaccination.

Epidemiology

Pasteurellosis incidence is dependent on three major factors:

Animal factors

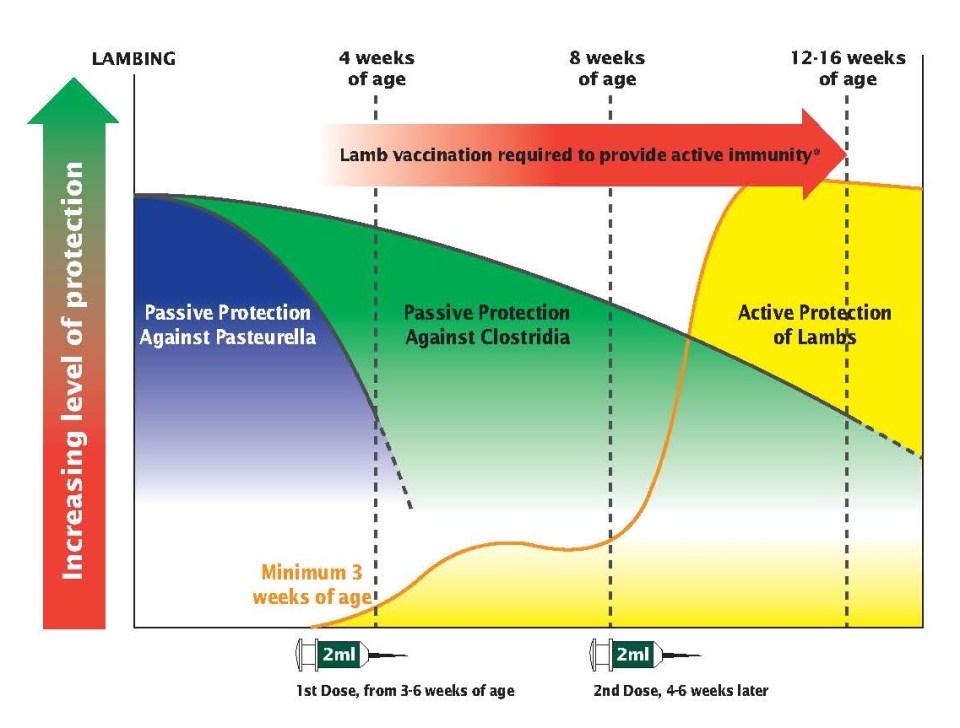

Colostrum is depleted by 3 months of age so passive protection waning leads to higher prevalence in this age group

The efficiency of an animal’s immune system may be reduced by stress from certain farming activities such as weaning, castration, transport or mixing and change in dominance hierarchy.

The age also influences incidence as the immune system and lungs are not fully developed until 12 months old.

Environmental factors

Air quality – Irritant dust & gases depress respiratory defences

Draughts stress animals

Humidity – High humidity favours dampness & disease spread.

Population density – Infective potential of respiratory disease increased with crowding.

Mixing of age groups facilitates disease spread from carrier animals

Mixing of animals with different disease exposure history facilitates spread to animals not previously exposed to that agent in the group.

Infectious agents – viruses, bacteria and parasites

Direct damage can be caused by certain infectious organisms such Mannheimia haemolytica, Bibersteinia trehalosi and Pasteurella multocida. Parasites can also contribute to significant disease by depressing immunity.

Clinical Signs

There are two distinct syndromes of pasteurellosis:

a) Septicaemia: Generally caused by Bibersteinia trehalosi, this condition is most commonly characterised by sudden death or the finding of moribund sheep. Treatment of affected cases is rarely successful. Outbreaks can be sizeable and result in significant mortality.

b) Pneumonia: During an outbreak of pneumonia, mortality in a flock can be as high as 25%. The disease is responsible for the majority of pneumonia in sheep and is a threat to all ages of sheep. Death and treatment costs can easily attain 8% of production costs. To this must be added the costs of reduced stock performance, sub-clinical illness and higher personnel costs.

Clinical signs are influenced by the age of the animal and mortality in young lambs can be very high.

Signs relating to Respiratory Disease

Fever (as high as 42 C)

Depression, laboured breathing and increased respiratory rate

Loss of appetite and cough

Reddening of the mucous membranes

Nasal discharge – Initially watery and later may become purulent

Conjunctivitis – runny eyes

Diagnosis

Diagnostics in respiratory disease / septicaemia can be based on

(i) clinical examination

(ii) laboratory testing

(iii) post mortem examination

(iv) preferably a combination of these different disciplines.

The clinical examination of diseased animals includes

· recording of respiratory rate and type

· rectal temperature

· observation for clinical signs

Clinical signs and gross pathology in respiratory disease only occasionally yield a specific diagnosis. Laboratory testing is often required for a proper diagnosis to culture the Mannheimia or Bibersteinia organism from the lungs (or septicaemic organs).

Laboratory tests can be carried out on samples collected

- from live diseased animals

- during post-mortem examination

LUNG WASHING: Two types of lung washing may be carried out: Trans Tracheal Lavage (TTL), involving insertion of a tube through the skin into the trachea or Bronchio-Alveolar Lavage (BAL), where the tube is inserted into the trachea through the external nares (nose). Your vet is best placed to conduct either of these diagnostic procedures.

Samples should be cooled during transport to the laboratory and transport times should be as short as possible

Post mortem examination to show the characteristic pathology (gross and microscopic) as well as culture of the above organisms is best for forming a definitive diagnosis.

Control

Control of ovine pasteurellosis is based on four equally important aspects:

- Management- Reduction of stress and circulating bacteria can be achieved with careful attention to detail. Significant issues in need of address include ventilation in housing, drainage, mixing of age groups, overcrowding and parasite control. Isolation of clinically affected cases and treating with an appropriate antibiotic can also limit losses.

- Biosecurity – Maintaining biosecurity involves avoiding introduction of infected animals into the herd and/or implementing stict isolation / quarantine of introductions until proven negative, and restricting access of livestock to external sources of infection e.g. double fencing is in place at all perimeters.

- Vaccination – The use of vaccines confers clinical protection and more importantly reduction of the pathogen circulation. Due to the complex cause of the disease and the fact that clostridia are common killers of sheep, multivalent vaccines are preferred. A number of inactivated vaccines with different combinations of antigens are commercially available. Vaccination programs should start at an early age e.g. from three weeks onwards to protect the young lambs. In situations, where protection is required for more than one winter season, it is advisable to re-vaccinate the animals at least 15 days prior to the risk period. It is critical that a primary course of two doses is administered when beginning vaccination or protection wanes (See diagram below). For further information on vaccination, please click here. Vaccination with Heptavac P Plus is preferred in breeding sheep as it covers a broader number of antigens while vaccination with Ovivac P Plus may be used in sheep destined for fattening. Ovipast Plus can be used in conjunction with clostridial vaccines to confer protection against Mannheimia haemolytica where a preference exists for broader clostridial cover (e.g. Tribovax 10). Consult your local animal healthcare provider for advice on the correct use of these vaccines.

- Treatment – Therapy is limited to the use of antimicrobials and anti-inflammatory drugs. It is often required to start the therapy before results of the bacteriological investigation are available and the resistance patterns are determined. Consequently, the bacteria can exhibit increasing resistance to a large number of antimicrobial agents. Preferably, antimicrobials which are active against Pasteurellae should be used.