PMWS

A page about porcine circovirus infection describing cause, clinical signs, diagnosis and control.

Introduction

PCVD (Porcine Circovirus Disease) is the name we have chosen to describe what was previously known as PMWS (Post-weaning multisystemic wasting disease) or simply “Wasting Disease”. PCVD is now recognised as a global, epizootic disease that causes significant economic losses to pig producers caused by PCV type 2 virus. PCVD was first diagnosed in Canada in 1991 whilst France was the first country in Europe to experience the disease. It is estimated to cost the pig industry an estimated €600 million per year in Europe alone.

Aetiology

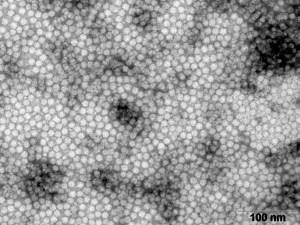

Porcine circoviruses are small DNA viruses that are classified as members of the Circiviridae family (photo courtesy of Dr. Jan W.M. van Lent, Laboratory of Virology, Wageningen University). There are two strains of the virus present, PCV1 and PCV2. PCV2 is generally considered pathogenic for pigs and PCV1 non-pathogenic. Other syndromes with which the circoviruses are associated are infectious congenital tremors, porcine dermatitis and nephropathy syndrome (PDNS), reproductive failure and subacute/chronic Proliferative and Necrotising Pneumonia (PNP). It was originally thought that PDNS (Porcine Dermatitis and Nephrosis Syndrome) was part of this disease complex though it has since been decided that, because both diseases can occur independently of each other, they are separate disease entities. Porcine circovirus 2 (PCV2), combined with stimulation of the immune system of the pig, has now been shown as the cause of PMWS

Epidemiology

PCV2 is considered ubiquitous and domestic and feral swine are considered the natural hosts. Natural infection occurs via the oronasal route. Disease occurs in all types of herds. Risk factors that trigger a worsening of disease may include, but are not restricted to, co-infection with PRRSV and porcine parvovirus, mixing of litters (which stresses pigs and exposes them to other new infectious agents), early vaccination against certain diseases and environmental factors, such as poor ventilation, overcrowding, or possible other ‘stressors’. Seroconversion of piglets to PCV2 generally occurs at 3-4 weeks post weaning. It can therefore be concluded that pigs are exposed when they are transferred to the fattening unit. While it seems that the virus is mainly transmitted horizontally, evidence exists to suggest that the virus can also be transmitted vertically

(dam to offspring). The virus is very resistant in the environment and a substantial number of disinfectants are ineffective against it.

There are a number of “known unknowns” concerning PCVD including the following:

• Disease occurs in a percentage of the infected animals only. Furthermore, while pigs diagnosed with PMWS are always PCV2 positive, not all PCV2 positive herds develop PMWS– why these are the case is currently unknown

• Severity of the disease can also vary enormously between countries or indeed regions. For instance, in some countries a high incidence of PCV2 positive herds is seen along with very few cases of PMWS. Significant effort has been made to differentiate strains to align with disease causing ability (pathogenicity) but, as yet, has not yielded any meaningful results.

• Seroprevalence, excretion patterns, incubation period and host range for PCV2 have not been fully elucidated. Excretion of PCV2 has been detected in faeces and saliva for up to one month post infection and possibly persists for longer.

Clinical Signs

PMWS is generally seen in pigs of 7-15 weeks of age and is generally considered over at 16 weeks…though recent reports have suggested disease post-weaning (as was initially described) and in heavy pigs. It is characterised by wasting, pyrexia, dyspnoea and enlarged lymph nodes. Pallor, icterus (jaundice), coughing, gastric ulceration, meningitis, diarrhoea and sudden death may also be seen. There is a high mortality rate in affected piglets most often within 48-72 hours after onset of clinical signs. Some survive a few weeks though recovery is rare if signs are severe. At necropsy lesions are present in multiple organs. High levels of viral particles in tissues leads to more severe disease while lower levels can lead to subclinical losses or even no problems at all. The reproductive form of disease is associated with:

- Abortions and/or stillbirths and/or mummified foetuses

- The presence of cardiac lesions in the foetus

- The presence of PCV2 in the cardiac lesions and other foetal tissues

b) As the disease evolves muscle wasting becomes obvious, there is dyspnea and a marked general lymphadenopathy. Other clinical signs include diarrhoea, pallor or icterus, pyrexia, coughing, gastric ulceration, meningitis and sudden death.

c) Most animals die within 48-72 hours after the onset of clinical signs. Some survive for a few weeks. Recovery has not been seen after the onset of severe clinical signs.

Diagnosis

Clinical signs

Clinical signs of wasting and associated lesions are quite distinctive though not diagnostic. Clinical severity can vary from mild to severe. Diagnosis should be confirmed by the following tests:

Post mortem examination (Necropsy)

It is wise to perform at least five necropsies from an affected group of pigs. If at least one of them has wasting, histopathological lymh node lesions and PCV2 detected in large quantites in lymphoid tissue then the herd should be categorised positive for PMWS. Lesions are noted in multiple organs. Lesions are variable. The most consistent lesions are seen in the lungs and lymph nodes. The lymph nodes are enlarged and firm. The lymph nodes are white on cut surface. Macroscopically the spleen is enlarged and meaty it is not congested on cut surface. Histologically in all lymphoid tissue there are changes in B and T cell populations with large amounts of PCV2 antigen detected in monocyte line of cells. Pneumonia is often seen in PMWS while the liver may show yellow-orange discolouration in cases of icterus or be markedly atrophic with prominent connective tissue. PCV2 antigen is detected in the cells. Renal lesions are seen in a number of cases. Kidneys are large and spotted with white foci.

Serology

ELISA based serology is only useful when paired sera, spaced 3 weeks apart, are tested showing a seroconversion. This must be accompanied by a report showing a concurrent increase in PCV2 related clinical disease occurring on the farm (See clinical signs above). Most animals seroconvert two weeks after infection so analysis in this way can give an accurate picture of timing of infection. In severe disease with subsequent mortality, moribund piglets may have low antibody titres as the immune system did not have an opportunity to respond prior to death.

PCR

PCR is the most sensitive test method to detect PCV2 virus and is highly specific. The quantitative PCR is particularly useful as disease severity is linked to viral titre in tissues. The isolation of PCV2 alone is not sufficient for the diagnosis of the disease. Care should be taken not to compare results from different laboratories using different methologies for quantitative analysis however.

Control

As this virus is quite resistant in the environment, hygiene of farrowing rooms is particularly important. An all-in/all-out policy should be strictly applied if not in place already. Hygiene of the sows by washing with shampoo as well as an anti-parasitic treatment before entering the farrowing room is advised. Cross-fostering should be avoided and if absolutely necessary should be restricted to within first 24 hours after birth. In the weaner houses, there should be small pens (containing <13 pigs) with solid partitions. Again, hygiene as above is critical. Stocking density should be no more than 3 pigs/m2. There should be adequate space at the feeder where dry feeding is practised (>7cm/piglet) while improving air quality is also worthwhile (NH3:<10ppm; CO2: < 0.15%., RH <80% etc.)

Temperature should also be maintained appropriate and constant, mixing of piglets from different batches should be avoided and sick pigs should be removed to isolation as soon as possible.

Vaccination is obviously the best and easiest way to protect weaners against PCVD. A variety of vaccines are available. Your local veterinary practitioner is best placed to advise you in this regard. Further information on the single component vaccine from MSD AH may be found by clicking here. MSD also markets a combined PCV and Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae vaccine. For more information on this vaccine please click here.